Space Pioneers

This summer, a space probe that launched nine years ago will finally reach its furthest destination of Pluto and the outer Kuiper Belt, sending back precious data and photographs. Space exploration is alive and well, and that’s partly due to the efforts of Oklahomans.

When Thomas Stafford was a child in Weatherford, Oklahoma, the word astronaut didn’t exist—but he knew he wanted to fly, and fly fast. After a test-pilot career, he was selected to make a trial flight to the moon on the Apollo 10, the precursor to the Apollo moon landing. The year 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of his historic flight during those early stages of space exploration.

Space travel began as a political race to beat Russia to the moon. Ten years later, Stafford initiated a mission in which the Soviet Union and the United States would join in friendship, in space. This July marks the 40th anniversary of that Apollo-Soyuz flight—Stafford’s last flight—which resulted in the famous space handshake between Stafford and Alexei Leonov. When Leonov was asked what language was spoken in space, he replied, “We speak three languages. We speak English. We speak Russian. We speak Oklahoman.”

Space travel began as a political race to beat Russia to the moon. Ten years later, Stafford initiated a mission in which the Soviet Union and the United States would join in friendship, in space. This July marks the 40th anniversary of that Apollo-Soyuz flight—Stafford’s last flight—which resulted in the famous space handshake between Stafford and Alexei Leonov. When Leonov was asked what language was spoken in space, he replied, “We speak three languages. We speak English. We speak Russian. We speak Oklahoman.”

In a phone interview from his Florida home, 85-year-old Stafford recapped his career. “I did the first rendezvous in space. During my second mission, my co-pilot did the first spacewalk around the earth. I flew the first lunar module to the moon and picked out the landing site. I set an all-time speed record coming back, and then did the first international rendezvous with the Soviet Union. It was an honor to represent Oklahoma during the pioneering days of space exploration. I thank God I had the opportunity to be there when we made all those giant steps forward.”

From the beginning, Oklahomans have embodied a pioneering spirit. Stafford told how his mother came to Oklahoma in 1901 after the Land Run to live in a sod dugout. “One generation later, she watched me go to the moon on live television,” Stafford said.

Bill Moore, film producer, writer and Oklahoma space historian said, “Oklahoma is a state born of land runs and pioneers—they were all looking for a new frontier of their own. It was their children and grandchildren who pioneered space.”

It was Stafford who was responsible for placing a color television camera on the Apollo 10, so that future generations could see the Earth in color. He explained that, “Earth was so beautiful from orbit that we needed to show it to the people, the American public, the world.”

It was the first and only time during his space flights that he felt strangely far from Oklahoma. Two days’ travel later, Stafford had his first glimpse of the moon, just sixty miles below. He described it in his autobiography as “bright and rocky…full of unfamiliar mountains and craters.”

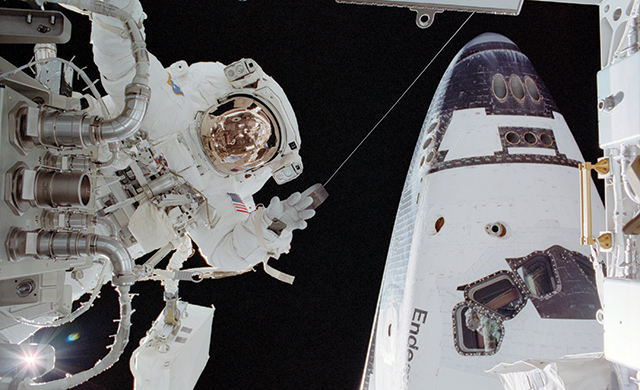

Oklahoma’s recently retired astronaut, John Herrington, was a child when he watched live footage of the moon landing on television. He remembers playing astronaut in a cardboard box, looking to the moon and dreaming about being an astronaut. Now, after having spent 330 hours in space, he looks toward space and thinks, “There’s actually stuff up there—people up there, people who have left things up there.”

E

ight of those people were Oklahoma astronauts. It’s a number to be proud of—but there’s a bigger story. Untold thousands of Oklahomans have left their imprint on the space program—without ever leaving the ground. Through technology, space probes continue to go boldly where no man has gone before—and Oklahomans have been there every step of the way.

“Oklahoma is the only state that’s had astronauts involved in every phase of the space program. I don’t want to give the impression that Oklahomans are the reason we got into space, but there was a great deal of effort by Oklahomans in space and on the ground to help make it all happen. Our engineers continue to touch every planet in the solar system,” said Moore.

Moore began interviewing Oklahomans when he realized that the original space explorers were quickly aging. He was determined to “get their stories while they were still alive.” It became apparent that in addition to astronauts, the 46th state had many engineers and technicians working for NASA. Then Moore started expanding his research to include politicians, geologists, NASA’s legal staff and administrators, mission control leaders like James Milton Heflin, a graduate of Edmond High School, and Jim Hartz, a reporter for NBC.

What makes Oklahoma such a strong contender in space exploration? Astronauts and space historians speculate that having a good ol’ Oklahoma farm-raisin’ provided the perfect training ground for the early space industry.

“A lot of astronauts and engineers from the 1960s were farm boys,” said Moore. “They graduated from Oklahoma universities, and they were 22- or 24-year-olds working in mission control making sudden life-or-death decisions. But they also knew how to solve problems, because when you’re on the farm, you don’t bring in a mechanic every time something breaks down—you get the bailin’ wire out.”

Moore shared the story of how the second moon landing was saved by an Oklahoman. At launch, lightning struck the spacecraft, and the electronics went haywire. John W. Aaron in mission control had seen the same thing happen in a previous test. From natural curiosity, he’d figured out a solution. One year later, 15 seconds into a multi-million-dollar moon launch, as the mission was about to be aborted, Aaron said, “Tell them to try the switch above the astronaut’s head.” It was an obscure switch hardly anyone knew about. The astronaut flipped the switch, everything came back on, and they went to the moon.

“NASA hired a lot of Oklahomans, and I think it was because they had a common-sense mechanical aptitude to solve problems,” Herrington said.

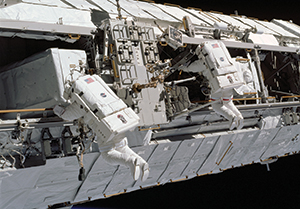

Herrington believes that he was selected for the International Space Station because of his rural raising and experience working with his hands. His credentials weren’t much different from all the other test pilots and engineers, but when NASA asked, “Why should we hire you?” he gave the winning answer.

“I’m different because I’ve been a tinkerer all my life. My dad is a great mechanic. My grandpa built a pump station with a third-grade education. This may sound corny, but I think the space station is the ultimate construction site. I would love to turn a wrench in space,” Herrington said. “I walked out thinking that I’d given a dumb, corny answer—even if it was from the heart.” But he got the job, and when a flight director said that the space station needed people who knew how to work with tools, Herrington thought, “I didn’t give such a dumb answer after all!”

Herrington laughed as he shared this story over the phone. He was driving home after serving as judge advisor for an Oklahoma robotics competition. “Right now, I’m driving a 1987 Volkswagen bus with a toolbox in the back, and if it breaks down, I’ll fix it. Some of these robotics students are coming from a ranch or farm, they have limited resources, but they can build a robot out of plywood and bailing wire!”

Currently, the manned space program is in a lull with the ending of the shuttle program, but NASA is just weeks from a close fly-by of Pluto. Experiments continue on the space station. Preparations are being made for further travel to Mars, and all predictions indicate that commercial tourism is on the cusp of becoming reality for the wealthy. Moore expects that Oklahomans will be involved in the next stage of space exploration. “We admire explorers like Christopher Columbus,” said Moore. “A hundred years from now, we’ll look back on these astronauts as pioneers—great explorers of the world.”

“Oklahomans have always been adventurous,” Stafford said. “What we did was new, unknown, never done before, but we understood the risks. It’s hard to believe it’s been 46 years since I was last at the moon.”

“I vividly remember being on the very end of the Space Station and looking over the Earth’s horizon, out into the vastness of the universe, and thinking there was nothing between me and whatever else was out there,” said Herrington. “It was a goose-bump-rendering moment that has profoundly influenced my belief that we can’t possibly be alone in the universe.”

The Gemini 6 spacecraft is on display at the Oklahoma History Center, or visit the Stafford Air & Space Museum in Weatherford, Ok.