A Soldier’s Story

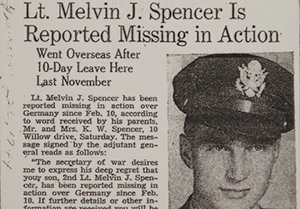

On the morning of February 10th, 1944, hundreds of B-17 bombers departed from England for Brunswick, Germany with orders to destroy a ball bearing factory. Melvin Spencer, a 2nd Lieutenant of the 8th United States Army Air Force, a navigator aboard one of those B-17s, was on just his fourth mission of combat duty.

The 8th Air Force had some of the highest death rates of any in World War II. In fact, the average lifespan for one of its airmen was 13 missions. Spencer’s B-17 was flying in “coffin corner”—the rear of the formation, so named because of its vulnerability to enemy fire and high fatality rates. He was, quite literally, in a death trap.

Soon after entering German-occupied territory, the B-17s came under attack by hundreds of German fighter planes, with catastrophic results. Six planes—including Spencer’s—had been shot down in 10 minutes. Spencer and seven of his fellow servicemen ejected the plane—two were killed. He landed near Osnabruck, Germany and was detained by civilians who would capture enemy combatants as a courtesy to the Nazis. “They took us into custody and were not abusive, fortunately,” Spencer recalls. One of his fellow soldiers, a radio operator, tried to convince Spencer that escape was their best option. “I told him that was suicide. Even if we did escape, we’d have to go clear across Germany, France and swim the English Channel!” Spencer realized the best course of action was cooperation, not provocation. “We had been issued a .45 caliber revolver by our superiors, but they told us to get rid of it if we were shot down. You didn’t want to give the Germans a reason to shoot you. They would.”

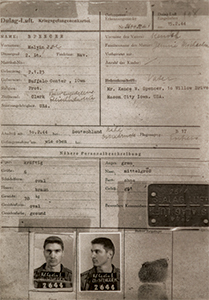

Spencer and other prisoners were held overnight in a warehouse in Osnabruck, then spent the next three days traveling to the Dulag Luft, an interrogation facility in Frankfurt. Spencer was held in solitary confinement for three days. He was then moved again to Stalag Luft, a prisoner-of-war camp in Barth, bordering the Baltic Sea on Germany’s northern shore. “Our trip was constantly interrupted because the Germans were always worried about Allied attacks,” he recalls. They arrived on February 20th, 10 days after Spencer was shot down.

Stalag Luft

Stalag Luft held nearly 10,000 prisoners of war at its peak. “Our camp was under the control of the Luftwaffe, not the SS. They were military men and treated us decently. We didn’t see any atrocities, but plenty of men were shot during escape attempts.” Many tried to tunnel their way out of the camp, but their efforts were fruitless. “The Germans always found the tunnels. Our commanding officer thought they had some seismic detection device to locate the tunnels as they were being dug.” Other prisoners took a more creative approach to escape. “One day we had a visit from the YMCA and Red Cross. One prisoner made his own suit and walked out with the contingent as they left the camp. He was gone for a few days before being captured. There were others that tried to escape, but no one ever got away.”

Stalag Luft held nearly 10,000 prisoners of war at its peak. “Our camp was under the control of the Luftwaffe, not the SS. They were military men and treated us decently. We didn’t see any atrocities, but plenty of men were shot during escape attempts.” Many tried to tunnel their way out of the camp, but their efforts were fruitless. “The Germans always found the tunnels. Our commanding officer thought they had some seismic detection device to locate the tunnels as they were being dug.” Other prisoners took a more creative approach to escape. “One day we had a visit from the YMCA and Red Cross. One prisoner made his own suit and walked out with the contingent as they left the camp. He was gone for a few days before being captured. There were others that tried to escape, but no one ever got away.”

He talks about his experiences in vivid terms, as if they occurred yesterday. Even at 93, he is able to recall with striking clarity the sights and smells of the camp. The food was particularly bleak. “They’d bring us a mixture of sausage, sawdust and leaves for breakfast. In the evenings there’d be soup or porridge with little or no meat.” Bread was given out in weekly rations, which were always substandard. The Germans would raid the Red Cross rations for prisoners of war, leaving Spencer and his fellow prisoners with whatever they didn’t want. Letters from home were few and far between—the Germans often discarded mail for American prisoners of war, and Allied forces frequently destroyed the German rail lines used to transport goods to prisoner camps.

The prisoners were left to make due with whatever was available to them. Cigarettes were frequently bartered for Red Cross rations, Spencer explains. “Card games, especially bridge, were really popular. Books from the Red Cross were, too, because everything else was printed in German.”

Liberation

Spencer remained in Stalag Luft for fifteen months until being liberated by Russian forces on April 30th, 1945. Spencer and his fellow prisoners had advance warning of the Russian advance via a shortwave radio in the camp, but they didn’t have specifics. The Allies were in the final phases of the assault on Berlin and the Third Reich was crumbling. By the time the Russians liberated his camp, Spencer’s German wardens had turned over control of the base to the prisoners.

Spencer remained in Stalag Luft for fifteen months until being liberated by Russian forces on April 30th, 1945. Spencer and his fellow prisoners had advance warning of the Russian advance via a shortwave radio in the camp, but they didn’t have specifics. The Allies were in the final phases of the assault on Berlin and the Third Reich was crumbling. By the time the Russians liberated his camp, Spencer’s German wardens had turned over control of the base to the prisoners.

“Our commanding officer, Col. Hubert Zemke, spoke fluent Russian and negotiated terms once they arrived.” Spencer, like many other prisoners, wasn’t aware that the Germans abandoned their posts and were pleasantly surprised to see American troops in the guard towers of Stalag Luft. Things could have turned out very differently, however. “The Russians wanted to march us down to the Black Sea and hold us as hostages for negotiations with the Americans, but our people negotiated our release.”

Spencer’s work as a soldier was not over, however. He was assigned to retake a German airfield—the Germans abandoned it—and spent his first days of freedom from Stalag Luft sweeping the vicinity for landmines and inventorying German munitions. “For about two or three days after that, it was a steady stream of us transferring out of there,” he recollects. He spent another two weeks at Stalag Luft before leaving Germany the same way he arrived—between the roaring engines of a B-17.

Oddly enough, Spencer wasn’t even supposed to be with the crew that was shot down that day in February 1944. “I had changed barracks and moved in late at night. A fellow officer, Ed Charles, helped me get settled, but I didn’t unpack my belongings. I was called at 2am to prepare for the mission because the other crew’s navigator was reappointed to be a lead navigator. I got up, went to breakfast, left for my mission and never came back.” Ed Charles would later write a short story based on Spencer, the soldier who ate his meal and seemingly vanished. Charles wore Spencer’s bomber jacket throughout the war, later donating it to a museum in the United Kingdom. In 1995, Spencer learned that the jacket was on display at the Red Feather Club 95th Bomb Group Museum in England. Spencer visited the museum in 2012 with his son Dennis and grandson Nathan. “I think they were afraid I’d take it back!” he jokes.

Home Again

Spencer returned home on July 1st, 1945. Like millions more, he used the GI Bill to fund his college education. He earned his undergraduate and law degrees from the University of Michigan before meeting his future wife Dena in Kansas City. The two moved to Oklahoma City in 1961 and have lived in the same house ever since. Like many veterans, Spencer is quick to praise the men he fought with before speaking of his own trials during the war. “I was proud to serve my country and have never regretted my service for a second.” Spencer repeatedly cites his faith as his saving grace during the war and remains a devout Christian to this day.

Spencer’s story, like thousands of others from World War II, must be preserved for consideration by future generations of Americans. His story reveals the best of his generation: grit, humility, determination and devotion to his fellow soldiers and his country. As the Greatest Generation ages, we owe them no less than to tell their stories for generations to come.